At last a guide that creates clarity out of the dizzying chaos of psychological and behavioural ideas buzzing around in recent years. It nicely mashes Gladwell’s Blink, Gilbert’s Stumbling on Happiness, Cialdini’s Influence, Ariely’s Predictably Irrational and Thaler and Sunstein’s Nudge into something you can read in a morning.

Essentially, MINDSPACE is a checklist of non-coercive behaviour change tools with proven robustness. The authors recommend policy-makers add them to the traditional mix of education, regulation and incentives and routinely consider their effects in any change in public policy. Why? Because, “Whether reluctantly or enthusiastically, today’s policymakers are in the business of influencing behaviour.”

For those who design behavioural projects, MINDSPACE is an authoritative introduction to approaches which can seem arcane.

Here’s the MINDSPACE checklist:

Messenger: The choice of messenger heavily influences our response to information. Often the disembodied voice of government is a poor messenger. Instead we should try using similar voices whose authority the audience trusts.

Incentives: incentives can make a difference but need to be approached with an eye to the science and careful audience research.

Norms: people are strongly influenced by what they believe others are doing, especially their peers. So use every chance to show that majorities are already doing the right thing.

Defaults: people are lazy and tend to accept pre-set options. So, for instance, ‘opt-out’ agreements result in vastly higher and more sustained take-up than ‘opt-in’ agreements.

Salience: getting people’s attention is the first step in a change project. People pay attention to the novel, surprising, humorous but tend to ignore the predictable. So don’t be predictable.

Priming: people’s immediate responses are influenced by subtle environmental and linguistic cues. So be aware of those effects.

Affect: emotion is an ever-present and highly influential part of any message. So use it.

Commitments: humans seek consistent public images. So promoting the actions that people have already done increases the chance they will act the same way in future.

Ego: the drive to like ourselves may be the most powerful human drive of all. So new behaviours which improve people’s public images or recognise their altruism are more likely to be taken up.

Which, of course, spells M-I-N-D-S-P-A-C-E.

Clean, readable explanations of the nine tools follow, plus case studies from fields as diverse as crime prevention, parenting contracts, littering, and contraceptive use.

Nice features of this guide

It’s packed full of fascinating case studies and nuggets of inspiration. For instance, did you know that building cycling trails is a far more cost effective health intervention than providing physical activity classes? [See the original journal article]

It’s full of nicely worded statements whose detail you might quibble with, but whose direction seems perfectly right, for example, “We recognise that the most effective and sustainable changes in behaviour will come from the successful integration of cultural, regulatory and individual change – drink driving demonstrates how stiff penalties, good advertising and shifting social norms all combined to change behaviour quite significantly over couple of decades.”(p13)

It critically considers the legitimacy of the MINDSPACE methods and the importance of seeking permission from citizens before to influence their behaviour. After all, since these methods work unconsciously they interfere with citizens’ time honoured “right to be wrong”.

It’s refreshingly free from the infatuation with Social Marketing that affects so much recent work coming out of the UK.

Intriguingly, it suggests that MINDSPACE “nudges” might be more socially equitable than information campaigns, because only the better off are capable of acting on information, whereas changing the context of behaviour affects everyone equally!

It admits there are questions about how long these effects last, and the yawning gap in our knowledge about how we make the shift from behaviour change to culture change.

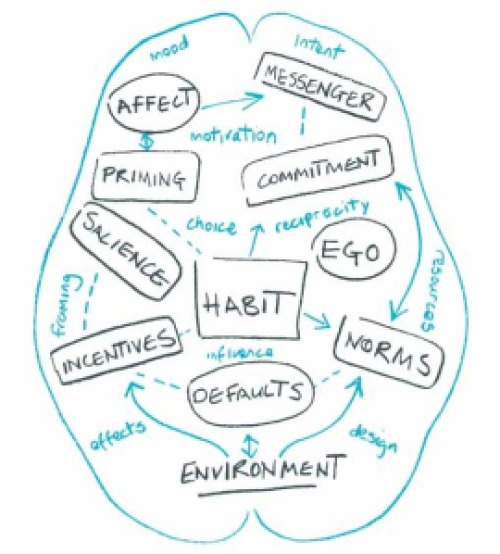

It has a marvellous spaghetti-gram (on p80) that demonstrates the fantastic maze of psycho-behavioural theories that confront anyone who works this field.

Weaknesses

The authors casually dismiss the role of social networks (aka viral or diffusion effects) meaning that they see behaviour change as a purely individual process. They are equally uninterested in the role of social organisation, social innovation and social leadership in enabling change.

Although they discuss legitimacy and permission they nevertheless gloss over the role of power. Who decides that a certain behaviour is desirable or undesirable? By glossing over power, they avoid the need to confront resistance, one of the biggest reasons why behavioural efforts fail.

And, like most efforts in this field, they forget that behaviours are designed and that some designs are fit-for-need and others aren’t. Learnings from Diffusion of Innovations and Design Thinking would help here.

Fortunately these are minor criticisms because the authors didn’t aim to create a holistic approach to behaviour change.

Overall

This is highly recommended guide for anyone working in the field of social change.

MINDSPACE – Influencing behaviour through public policy, from the Institute for Government, UK